Previous sections have called attention to the limitations of the academic research paper and the need for a range of research outputs.

In this section, we investigate the barriers to innovation within research presentation, covering issues related to budgets, career priorities and academic culture.

Professor Debbie Isobel Keeling, Associate Dean of Engagement, University of Sussex Business School, offers her views on the traditional article and ways to mobilise knowledge. She believes that to reach different audiences, the academic article should be complemented by a variety of content and services.

On this page

- Why budgets and career priorities are hindering progress

- Money worries

- Who pays for innovation?

- Is progress limited by academic culture?

- Are academic traditions holding back early career researchers?

- Lack of investment in technology

- Expert view: How can research be more valuable to wider society?

In the report

Why budgets & career priorities are hindering progress

Many of the barriers that prevent innovation within research presentation and teaching are linked to academic culture. Academics are constantly managing multiple responsibilities; they must apply for and win grants, research, write papers, publish (preferably in high-impact journals), and teach. To increase their chances of progression, they need to find time to network, collaborate, present at conferences, as well as engage the public and reach out to policy makers.

Alongside their responsibilities, academics often face uncertain futures. In the UK, with higher education under pressure to reduce costs there is a tendency to employ academics on a casual basis. 34% of academics were hired on fixed-term contracts in 2018-19, according to the most recent data from Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA). Casualisation within the sector could increase in the future, as universities face even greater financial uncertainty due to the COVID-19 crisis.

Academics across the world face similar employment insecurities as more universities embrace the trend to casualise staff. In Australia, some of the country’s best universities have the majority of their academics on fixed or casual contracts, and younger academics tend to be most affected. In some universities more than 80% of staff below the age of 30 are on insecure contracts.

Money worries

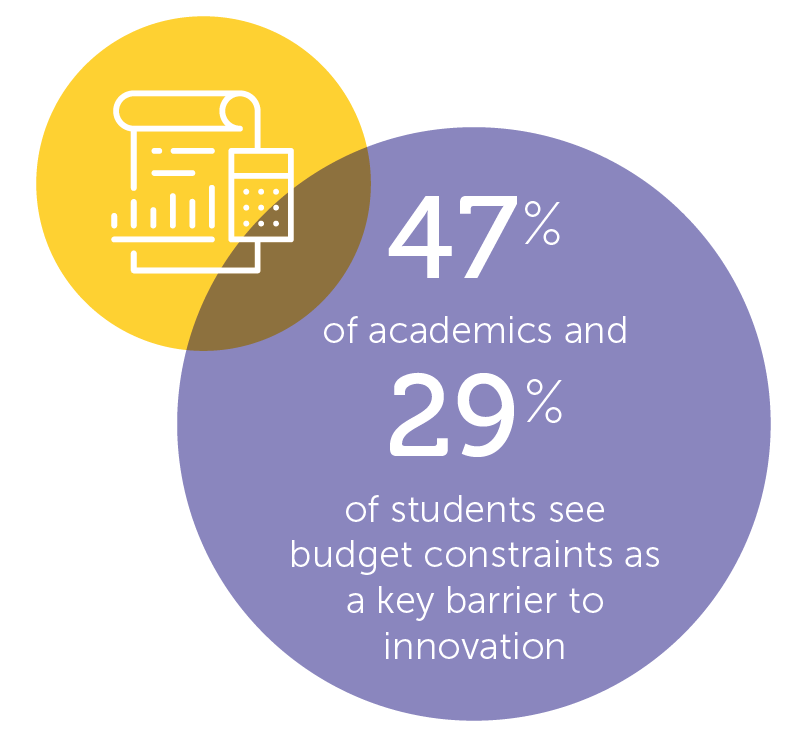

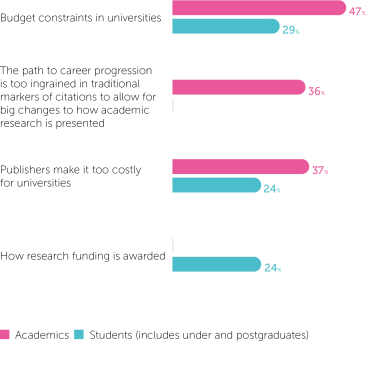

Limited university budgets are a major barrier to innovation for academics. While funding is more of a concern for academics (47%), 29% of students (rising to 42% of students in Brazil) also recognise that budget constraints hinder change.

Academics in India are particularly worried about budget constraints in universities, with 69% selecting it as an extreme barrier to innovation.

In China, 11% of students chose budget constraints as an extreme barrier, but this rose to 45% of academics in China and East Asia.

Thirty-seven percent of academics believe publishers charge universities too much and 36% (rising to 58% in Australasia) share concerns around how research funding is awarded.

Who pays for innovation?

Sixty percent of academics think the cost of new content forms should be covered by Article Processing Charges. However, 14% of academics are prepared to pay more if new content forms are likely to improve the impact of their research, and 11% agree to pay more if additional costs are under 10%.

Is progress limited by academic culture?

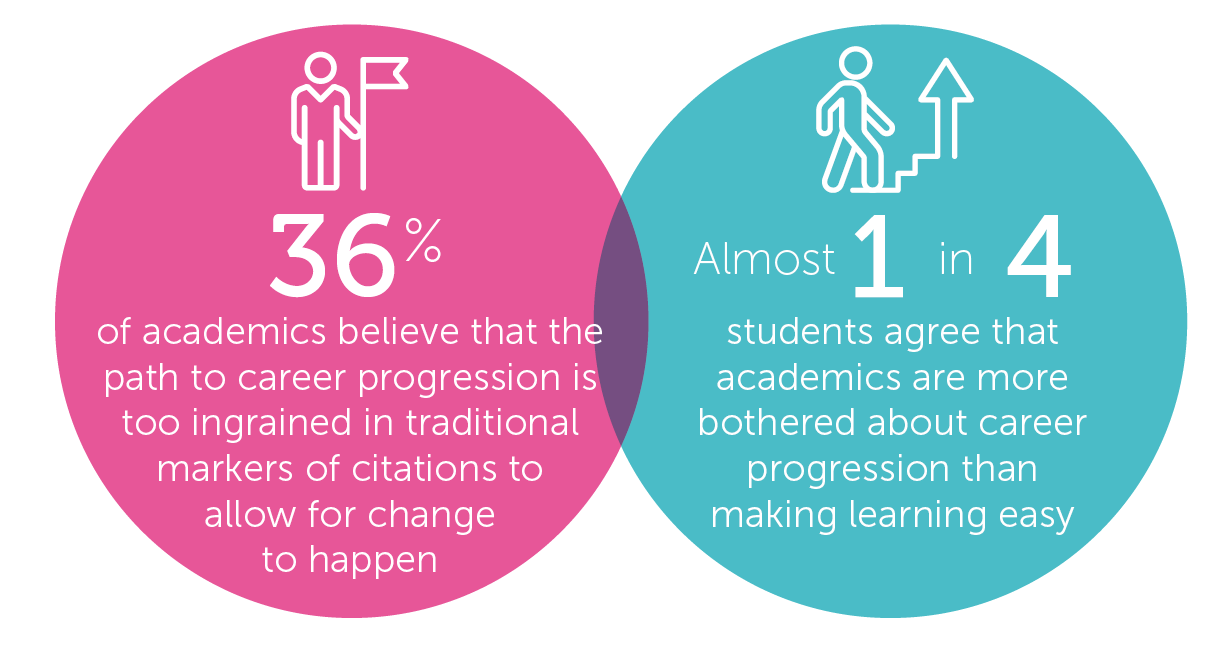

Over a third (36%) of academics feel that the traditional path to career progression hinders progress on how research is presented. Academics in Australasia and North America are most inclined to agree that the academic incentive system is an obstacle to innovation. What is most striking here is that researchers place the responsibility for lack of innovation on the system, whereas almost a quarter of students believe the responsibility for inaction lies with academics themselves.

Both groups to some extent believe there is a resistance to change within academic culture. 31% of academics and 23% of students agree that academic culture is very traditional and isn’t keen on change and/or that academics have an old-fashioned mindset and don’t like change. This barrier was felt most strongly by 47% of academics in North America and 45% of students in the USA.

Are academic traditions holding back early career researchers?

'They [ERCs] need to be disruptors and innovators since the beginning. This means that, sadly, we must accept that shining future minds will be more practical, less theoretical, more prompted but less accurate.' Academic in South & Eastern Europe

'1. They don’t have the resources needed to break into the system. 2. They are judged by traditional peers (tenure and promotion). 3. Research funding goes to traditional researchers with reputations for success using traditional methods.' Academic in North America

'The reward structure for tenure in higher education is biased toward traditional measures which seem to be increasingly “traditional” in their nature. For example, many institutions want to require an impact index for research, which is a flawed process of counting peer citations.' Academic in North America

Lack of investment in technology

Thinking about innovation in the way that academic research is presented to new generations of learners, please state how much of a barrier you think each of the following are in achieving this innovation.

| Response | Academics % | Students % |

|---|---|---|

| Budget constraints in universities | 47 | 29 |

| The path to career progression is too ingrained in traditional markers of citations to allow for big changes to how academic research is presented | 36 | 0 |

| Publishers make it too costly for universities | 37 | 24 |

| How research funding is awarded | 36 | 22 |

| Academic culture is very traditional and does not like change/academics have an old-fashioned mindset and don’t like change | 31 | 23 |

| How research quality is measured e.g. too much focus on citations | 30 | 19 |

| Out of date technology | 17 | 25 |

| Academics are more bothered about their career progression than making learning easy for non-academics / students | 0 | 24 |

One in four students believe that out of date technology hinders progress in innovation, compared to just 17% of academics. Out-of-date technology, is a barrier most felt by students in Brazil (38%), India (36%) and the USA (33%), whereas, students in Japan (6%) and China (9%) see it as less of an obstacle. Academics in the Middle East and Africa (29%) most strongly see outdated technology as an extreme barrier, followed by 24% in India.

See regional breakdowns of participants in this report for academics and for students.

Expert view

Professor Debbie Isobel Keeling – Associate Dean of Engagement, University of Sussex Business School – asks how can research be more valuable to wider society?

We need to ask, as any business would, what is our product and how is this valuable to wider society?

The nature of published content undoubtedly needs to be broader in format to meet the differing demands of audiences. The one-size-fits-all research article is not a sustainable model.

This is evident in the results of this survey. Articles are important as a way of mobilising knowledge in academia, but academia is not the only ‘user’ of research. Instead, articles are one part of what should be a wide portfolio of content and services that meets the different needs and purposes of our societies. For example, sharing of proven teaching / training methods sits alongside consultancy services for SMEs.

This is a long-term change, but is supported by the drive for greater societal impact, and will demand some uncomfortable transitions. Our use of metrics will change dramatically over the next 10 years, as we move away from assessment of quality through numbers towards assessments that are more qualitative in nature. Increasingly, research is being measured in terms of impactful outcomes, rather than impactful outputs.

We no longer operate in a world where the one-size-fits-all research article is a sustainable model. This is evident in the results of this survey. Articles are important as a way of mobilising knowledge in academia, but academia is not the only ‘user’ of research. Instead, articles are one part of what should be a wide portfolio of content and services that meets the different needs and purposes of our societies

We will need to develop a non-limiting framework for impact that allows its value to be understood by stakeholders. Career pathways will do much to drive these changes and to bring diversity to the way in which academic work is conducted and delivered, with impact on our ‘product’. More fundamentally, embracing representatives of broader society as co-creators in the research process will completely change the conversation. With this, the outputs and outcomes will no longer be delivered to ‘users’ but co-created with society. The result will be ‘fit for purpose’.

Publish with us

Choose the right home for your research across our journals, books, teaching cases and open access options. Follow our guides and find the right resources to help you submit, publish and promote your work.